(Please note this is a long blog post in order for me to do this subject justice. It’s likely to be of most interest if you have experienced adverse meditative affects)

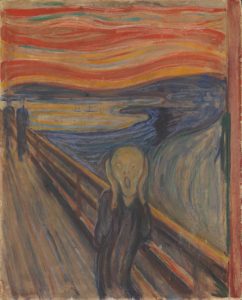

Meditation is not all spa music, oxytocin, sandalwood and light! There can be stages that are like arduous rights of passage. A shamanic  vision quest. There might be underlying mental health pathologies that mean that practice, or at least intense practice might be unwise.

vision quest. There might be underlying mental health pathologies that mean that practice, or at least intense practice might be unwise.

Yet in the west mindfulness has been marketed as a panacea (although it is already facing a backlash in the press like and also). But traditional practices are well aware of these potential challenges. For a start, many schools of meditation aim at ‘deconstructing the sense of self’ and ‘realizing emptiness’ which clearly are not the same as relaxation and improving corporate performance. Take for example a classic manual from the meditative world:

‘At the peak of insight knowledge of dissolution, one clearly realizes that mental and physical phenomena vanished in the past, are vanishing in the present, and will also vanish in the future. As a result, conditioned phenomena begin to appear fearful. At this point insight knowledge of fear arises’ (Mahasi Sayadaw, Manual of Insight). This is followed by the insight knowledge of danger when ‘conditioned phenomena’ will be experienced as ‘unpleasant, detestable, and harsh’. This is from one of the traditional Burmese teachers that the modern mindfulness movement has in part grown out of (Zen and Vipassana being Jon Kabat-Zinn’s main practices before developing MBSR).

The brilliant Neuroscientist and Zen practitioner James Austin describes in Zen and the brain, Makyo, which is the Zen traditions version of side effects of meditation. He states Makyo is ‘what can happen when the brain opens up the barriers which would otherwise separate its states of waking, sleeping and dreaming’. And ‘intensive meditative concentration for weeks or months invariably yields visual or auditory aberrations, hallucinations, or unusual somatic experiences’. In Zen training, students are taught to disregard Makyo and to continue with the practice no matter what happens.

In Tibetan Buddhist traditions, this category of experiences is known as Nyams and can mean everything from visions, psychological distress, physical pain, paranoia and terror. There are a number of famous western Tibetan teachers who have talked about intense adverse experiences after doing the traditional 3-year retreats that are part of the Tibetan path. From shamanic practices to the pragmatic dharma of modern ‘hardcore practitioners’ you find the equivalent stages in almost every spiritual practice involving contemplative practices. In their highly engaging book ‘The Science of Meditation’ Daniel Goleman and Richard Davidson state ‘dark nights are not unique to vipassana; most every meditative tradition warns about them. In Judaism, for example, Kabbalistic texts caution that contemplative methods are best reserved for middle age, lest an unformed ego fall apart’. There are even studies that show long term practioners can experience many of the same ‘symptoms’ as depersonalization disorder (DPD) but without the negative affective (emotional) tone.

The brilliant Neuroscientist Willoughby Britton of Brown University has been leading pioneering work in this field in the Varieties of Contemplative Experience Study (VCE). Britton began researching solely on the positive side of mindfulness for wellbeing, but after directly experiencing patients suffering from severe adverse effects she started to look at this area. Supportive of mindfulness, Britton is keen that it is not framed as a panacea and the nuance of these powerful practices are understood (as they are rolled out en masse as mental health interventions). She interviewed long term meditators including expert teachers from a wide range of practices (Zen, Theravada, Tibetan). Her team found that there was a huge range of experiences both cognitive and somatic and the emotional valence ‘ranged from very positive to very negative, and the associated level of distress and functional impairment ranged from minimal and transient to severe and enduring’. She receives multiple phone calls a week from meditators experiencing issues and has set up a support group and in the beginning of her work she even had long term severely impaired meditators staying in her house to recover.

On top of this there are endless accounts of seemingly ‘high level’ teachers who end up doing unforgiveable things, that speak of mental health difficulties. Some of this element is explored in the Buddha Pill, in which Dr Miguel Farias and Catherine Wikholm examine this aspect in detail and other shadow sides of meditation. I think this is a book that is worth all meditation teachers having a look at in order to gain a mature view of their art. It attempts to give a balanced assessment on what meditation can and cannot do for mental health and life at large. They have a chapter examining the ‘dark night of the soul’ and interestingly they note that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has had a clause noting mental health problems, such as depersonalization, may arise as a temporary result of spiritual practices. Working with Dr Farias there is a meditation group in the UK headed by Damcho Pamo who experienced her own psychosis and mania after attending a Zen retreat, and now seeks to support others. There website speaks of some of the potential adverse effects in a balanced and supportive way.

Now clearly as a mindfulness teacher, I am a fan of mindfulness, but I am keen that we take a sensible approach to how we use it for improving mental health. It is not a panacea. Much like physical exercise not everyone can start training for a marathon right away or compete in crossfit. Some people may carry injuries that need physiotherapy first and for some people they might have to adapt their physical training to match their genetic body type and vulnerabilities. I think this is a useful analogue for intensive meditation practice. Briefly my own story with adverse effects includes experiencing anxiety, panic, OCD, depression and depersonalization from a young age (many of my earliest memories were panic attacks). Some of these challenges definitely brought me to practice Zen and Qigong twenty years ago in an attempt to heal myself. And as I practiced through the years I learned tools that helped me manage my anxiety (although it wasn’t till I had CBT that the pieces came together to help me).

Many of the earlier years in practice I would experience intense emotions, pain from long sits and other adverse experiences and I got pretty good at sitting with these. I did a number of silent retreats which I practiced intensely through each day from waking to sleeping for 9 days. I would do extra sits, sit through part of the night and engage in ‘strong determination sitting’ which for someone with early onset arthritis meant a lot of knee and back pain. For many years’ depersonalization had not been a major feature of my mental health challenges, then after a retreat for the following months I was trying to sit as much as I could and practice through the day, then I had an intense adverse experience. I had levels of primal terror I had never experienced before, sensory alteration, existential anxiety, strange somatic experiences, depression, depersonalization more intense than I had ever experienced and many other symptoms. This period coincided with other intense life trials like the intensity of psychotherapy training, a number of bereavements and life choices so I believe it was a combination of causes following a lot of intense practice.

Many of the earlier years in practice I would experience intense emotions, pain from long sits and other adverse experiences and I got pretty good at sitting with these. I did a number of silent retreats which I practiced intensely through each day from waking to sleeping for 9 days. I would do extra sits, sit through part of the night and engage in ‘strong determination sitting’ which for someone with early onset arthritis meant a lot of knee and back pain. For many years’ depersonalization had not been a major feature of my mental health challenges, then after a retreat for the following months I was trying to sit as much as I could and practice through the day, then I had an intense adverse experience. I had levels of primal terror I had never experienced before, sensory alteration, existential anxiety, strange somatic experiences, depression, depersonalization more intense than I had ever experienced and many other symptoms. This period coincided with other intense life trials like the intensity of psychotherapy training, a number of bereavements and life choices so I believe it was a combination of causes following a lot of intense practice.

Ultimately this experience was positive in that it made me look deeply at my life, how I was practicing and what was meaningful to me. From an acceptance and commitment frame I was far away from many of my values, isolated and practicing meditation excessively. It also increased my empathy for those suffering from intense mental health disorders. It helped me refine my understanding of using mindfulness to help recovery from mental health issues, and how to adapt the practice for anxiety disorders and other mental health problems. Interestingly I’ve had no students have these types of experiences in 8 years of teaching. Occasionally I have had someone experience a heightening of stress in the beginning of mindfulness practice, normally when they are living a stressed and busy life in London. However, I think the intensity of my experience followed about 15 years of disciplined practice (practicing many hours a day), a number of retreats and a number of months of attempting continuous practice through much of my daily life. As I write this its obvious how out of balance and obsessive my approach had gotten.

Here are some suggestions based off my own experience. The first being to consult a trained mental health professional (ideally one that knows this territory) if you are experiencing difficulties:

- Significantly reduce your practice time. I would advise anyone experiencing adverse effects to slow down their practice, and significantly reduce the time spent sitting. Even cut the practice down to 5 minutes or 3 minutes or take a break from practice. If you do decide to keep going, then make sure you are working with an advanced meditation teacher who understands this process. For example, for the teacher training at Spirit Rock – head teacher Jack Kornfield makes all teachers do training in the trauma therapy approach Somatic Experiencing. But honestly, I would say don’t continue on retreats or intense practice if you are having adverse effects. Get back into your life and make your practice a smaller supporting part of it.

- See a professional, ideally a therapist skilled in this area and often they will be a trauma therapist trained in modalities like Somatic Trauma Therapy, Sensorimotor Therapy or Somatic Experiencing. David Treleaven book Trauma Sensitive Mindfulness is a brilliant resource here (and a must for anyone teaching Mindfulness or Meditation). Also, Babette Rothchild’s The Body Remembers part 2 has excellent guidance on how to adapt mindfulness for individuals who have experienced trauma. She suggests the areas of high risk with MBSR training being: ‘the rigidity of program structure and task instructions; the inward focus of mindfulness targets; the length of practice sessions; postural positions for practice and the possibility of relaxation-induced anxiety for people with PTSD, anxiety or panic disorders’. She recommends more agency and control for the student to adapt the practice, placing focus on the ‘exteroceptors’ of sight, hearing, taste, touch and smell. PTSD sufferers are often overwhelmed by their ‘interoceptor’ sensations when focusing inside their bodies, she even suggests potentially switching back and forth between the focus from inside to outside the practitioner (which I found useful myself). The portions, pacing and positions are important with recommendations to engage in mini practices, adjusting to postures which don’t trigger sufferers (lying down or sitting still can trigger freezing in PTSD) and promoting practitioner agency.

- Focus on life goals and values. The teachings from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy particularly focusing on value-based actions is really useful here. We can use our meditative skills to accept difficulties and then focus out into the world and engage with life. Don’t spend long periods of time focusing deeply on your symptoms in an attempt to ‘see their impermanence’. There are certain experiences that may just be too much, and you are better to use acceptance and then read a good book or speak to a friend. Can you build acceptance towards your symptoms of depression, anxiety, DPD etc and engage in a meaningful life? Here we use the skills of meditation to direct our attention out in the world.

- Reduce self-focus. Linked to this is the negative impact of excessive self-focus found in many mental health issues. Intense meditation practice can potentially exacerbate this and the more we can train our focus out into the world the better. Many Cognitive Behavioural Therapy experts emphasise training this external focus. Particularly I got a lot from David Veale and Rob Wilson’s work on reducing self-focus, their books such as Manage Your Mood and Overcoming Health Anxiety have a lot of useful techniques for dealing with adverse effects linked to excessive self-focus. Techniques such as attentional training and situational attentional refocusing.

- Try some different meditative approaches – if the breath feels uncomfortable and panicky then you could switch to different anchors for example physical sensation of sitting, sounds, gently staring at a rock or candle. If closing your eyes seems destabilising then you can open your eyes. You could try visualisation practice and imagery like Compassion Focused Therapy imagery. You could even use thinking to describe the image in compassion focused or safe place imagery thus engaging the language centres of your brain whilst meditating which I think can be helpful. You could use an app on your phone to lead you in breathing exercises as engaging with an external source can be useful. Loving Kindness practice might be a better choice right now (although people do have adverse effects from this practice), I found switching to this practice is shorter doses was particularly helpful.

- Rotate between meditation and thinking. It’s important to have both approaches online, in fact there can be an overlap between intense meditation practice which quietens the default mode network (often described as a beneficial quietening but more nuanced in reality) and symptoms of dissociation. Sit for a while, say 10 minutes and then either let your mind wander or actively think about things. Maybe switch back and forth between meditating and thinking. This can help your brain move more easily from a quiet default mode to a more active one. Another approach I found useful was to sit for a while and then read a fiction book or watch a tv show. This is similar to Babette Rothschild suggestion of switching between an internal focus and an outside focus (mentioned above) but also engages the language centres of the brain. Linked to this is using affect labelling which I mentioned in previous blogs. I particularly think compassionate thinking is brilliant here. The brilliant Scott Barry Kaufman has written a lot about the (highly relative to this point) concept of positive constructive daydreaming.

- Working with a blank mind. To build on the above step, a lot of people who experience adverse effects and depersonalization, experience having a blank mind – but not in a positive way. It’s like the anxiety response has shut down thinking (similar to a trauma response), or thoughts are so vague and nebulous that you can’t really find them (these experiences can be reported as positive things in meditation, but for many people they can be terrifying). In this case it can be helpful to re-cultivate the ability to think. Sub-vocalising or even saying thoughts gently can help, reading books as slow as you need to in order to engage and possibly reading out loud. I particularly like the concept from compassion focused therapy technique of compassionate thinking, or Barbara Fredrickson’s concept of narrating your day in a kind way. Just building acceptance of your mind and how you are feeling whilst engaging in thinking about your current task can be so powerful here.

- Working with relaxation induced anxiety. When I began practicing qigong and meditation many years ago I experienced a lot of relaxation induced anxiety. Through many years of practice and exposure this reduced, although I would still occasionally experience it when I did long sits or got into deeper states of relaxation and concentration. When I experienced some adverse effects I found Prof Paul Gilbert’s advice from his brilliant book Overcoming Depression really useful. He describes for people who find either breathing or relaxing to invoke anxiety, that it can be a useful practice to do slow soothing breathing and progressive relaxing whilst doing another activity. This can be something more physical like walking or gardening, or a relaxing soothing activity like having a bath. You can even squeeze a ball and have your focus on touch and the breath and relaxation in the background. Additionally, alternating between tension and relaxation as per progressive relaxation can be useful, and practicing yoga that might actually strengthen, solidify and tense your muscles.

- Movement can be incredibly powerful. For example Hans Burgschmidt, as told in Jeff Warren’s brilliant article (worth checking out Jeff’s other work as well) various types of physical practice were key to Hans recovery. The most ideal thing is if we can engage in a group-based activity, in nature which we find engaging and physical challenging. Too much time on our own spent exercising might not be the ideal practice here. I think it’s great to do a combination of slower more meditative practices and also more intense exercise (cardio and strength training). Exercise is such a great support to our mental health.

- Practice Gratitude and other more ‘cognitive’ practices. This means engaging meditative practices which actively keep our thinking and conceptual faculties on line. Sometimes the non-conceptual awareness of meditation is not what you need for robust mental health. This is where gratitude and savouring practices from positive psychology come in handy. We do a meditative practice when we actively reflect on the details of the different things in our life we feel grateful for, and we also tune into the feeling of gratitude in our body and hearts. In savouring we can cognitively reflect on what we are enjoying in the moment and subvocalize phrases that reflect this like ‘this feels good, I love doing x/y/z’ whilst savouring the pleasant aspects of our present moment experience. Also, the visualisation and imagery practices as found in Compassion Focused Therapy might be useful here.

- Reading novels and enjoyable literature, and engagement in enjoyable hobbies. I found that in my difficult periods I was compulsively reading a lot of books on meditation, philosophy, psychology and consciousness science etc. For now, it would be worth putting down these books, stop listening to podcasts on these topics and step away from the YouTube dharma talk! If we focus on this it can continue to send the brain signals that we are trying to solve this uncertainty (around existence, the self, life, our symptoms etc) and it will keep the anxiety going that feeds the depersonalization. By all means you will be able to get back to reading and studying this material, but ideally in a more balanced and less compulsive way. For now reading enjoyable novels, engaging in artistic pursuits, learning a musical instrument, listening to enjoyable audio books might all be a better choice for your tired brain.

- Join your community, and find connection. As is the case with many aspects of mental health, human connection is a key part of recovery. We are wired to connect and often people experience adverse effects in meditation when they may be isolated and lacking meaningful connections. I think that retreat practice can be a brilliant way to build mindfulness skills but often adverse effects occur in the retreat setting. Most retreat centres screen for mental health issues, but the silence and hours of intense practice are not the right approach for everyone. Be honest with yourself as to whether this is the right choice for you. Even the famous podcaster Tim Ferris experienced adverse effects on retreat, which he reports to be ultimately healing and leading in a positive direction, but were intense none the less. So, make sure you are connected and in community to support your practice. Join a group, especially one with teachers who are familiar and experienced in working with adverse effects. Maybe you would be better to practice being in the moment with awareness whilst listening and talking to a friend rather than sitting in silence. This was undoubtedly a part of what led to my experiences. In Jeffrey Young’s schema therapy, there is the concept of the detached protector mode that patients can experience. People who have experienced attachment trauma in childhood, learn to withdraw and depend on themselves. Experiences like DPD are often a part of this mode, in order to break this pattern, we might need to push against this isolated protector and connect with others. This could be part of a mindfulness practice, to engage in mindful and compassionate connection with others.

- Be kind to yourself, don’t just sit through emotional adversity. As with a lot of my approach to mental health, self-compassion sits at the heart of it. There are many teachers who will just advise students to sit through any intense experience and develop mindfulness with it. You have brilliant teachers like Mingyur Rinpoche and Joseph Goldstein who both talk about using anxiety their own anxiety and panic to develop mindfulness, sitting and observing it closely. This is not always appropriate advice for everyone as demonstrated in some of the accounts I have linked to and in the trauma work of Treleaven and Rothschild. In my own experience I had levels of anxiety that I sat with, it was not uncommon for me to sit for an hour or longer with anxiety watching my body and mind and building acceptance. But then I hit levels which were far too overwhelming for me to sit with, the more I sat the more they would be the dominant emotion throughout the day and would intensify and disrupt my functioning – making me experience more intense levels of depersonalization and depression. What was better was to accept these emotions and then actively pursue meaningful activities in the world with people I care about, using meditation to focus out into the world rather than into myself. Teachers who advise this approach may not have experienced trauma, may not be prone to depersonalization and may have a very different brain to you. More sitting is not always better. Sometimes it can be better to use your meditation skills to accept challenging emotions and bring your focus to reading a good book, art or music or talking to a friend. Don’t spend a lot of time observing difficult thoughts and feelings (it’s easy to get tangled with old memories, or to amplify the fear through somatosensory amplification) instead label and passively disengage and then place your attention on something positive and meaningful to you.

- Exposure and response prevention can be useful. It’s worth getting professional help with is aspect. If you have existential rumination/ocd alongside your issues it might be helpful. From talking with others and reading accounts of adverse effects there can be a connection to existential rumination typical of obsessive-compulsive disorder. This was the case for my own experiences. This is often pertinent in depersonalization disorder as described in the brilliant Overcoming Depersonalization Disorder by Katharine Donnelly and Fugen Neziroglu (a book that I think is a must for anyone suffering from adverse effects along with Elaine Hunter’s DPD Book). Exposure was even a path of great meditation masters like Ajahn Chah meditating in charnel grounds and exposing themselves to existential fear.

Sometimes these existential ruminations are what keep the adverse effects going. There is excessive self-focus and checking of how we feel, intense reading of meditation literature or videos that discuss whether the self is real, whether we have agency, is life ultimately suffering etc all tangle together to feed the DPD. When the meditator is not practicing they might be ruminating on deep existential questions that have not been answered by anyone, that might cause terror and anxiety which further feed the issues. Sitting under this may be fears about losing ones mind, living an unhappy life or brain disease leading to death. As with other forms of OCD exposure and response prevention can be key here. For example, you can write out and read through an exposure script that runs through the worst-case scenario ultimately leading to mental breakdown, misery or death (Donnelly and Neziroglu’s book is an excellent guide on how to do this step). It can also be good to write exposure cards or to agree with these thoughts and expose yourself to them in the moment as per this excellent article by CBT expert Fred Penzel.

Then the response prevention means you use your meditative skills to accept the initial obsessional thought and then do not engage in the rumination of trying to solve these unsolvable mysteries of life. For this step, what has seemingly caused the issue is the tool to get out of it, i.e. the attentional skills developed through meditation. This is not to say that there is not a place to ponder life’s mysteries but generally people doing this are able to shut off their thoughts after some time of pondering, or these thoughts don’t cause intense anxiety or depression typical of DPD. You will be able to come back to pondering these questions and reading from time to time but for now it would be wise to reduce or stop any compulsive ruminating or reading on this topic.

I think adverse effects can be caused for a variety of reasons. They might be as simple as you are living a stressful life and its only when you sit still you notice how stressed and anxious you are. It might indicate that you have a trauma history, that mig ht not be known to you, and that this might be resurfacing (this can be healing when it is done at the right pacing with a professional). They might be natural effects of deep and intense practice as have been described through the ages, and depending on how you frame them and how ‘robust’ your sense of self is, you might move safely between these ‘no-self’ states and daily life. They might also relate to individual genetic makeup and brains. For example, in the DPD world a lot of people are triggered through taking drugs. And this demonstrates how different brains can react to different stimulus, as many people take drugs without experiencing DPD, it could be the same with intense meditation practice. It could reflect other underlying mental health issues, or your vulnerabilities from your childhood attachment histories. Clearly it is a complex topic and I’m sure the work of scientists like Britton will begin to shed light on the nuances so that everyone can benefit from the positives of meditation at the right ‘dose’ and pacing. Some people never experience this territory, others do for brief periods without major impact to their lives, but some people do get stuck in these modes for long periods of time. Hopefully especially the latter group will benefit from ideas in this post. Feel free to contact me if you have any queries about adverse effects as a result of meditation practice.

ht not be known to you, and that this might be resurfacing (this can be healing when it is done at the right pacing with a professional). They might be natural effects of deep and intense practice as have been described through the ages, and depending on how you frame them and how ‘robust’ your sense of self is, you might move safely between these ‘no-self’ states and daily life. They might also relate to individual genetic makeup and brains. For example, in the DPD world a lot of people are triggered through taking drugs. And this demonstrates how different brains can react to different stimulus, as many people take drugs without experiencing DPD, it could be the same with intense meditation practice. It could reflect other underlying mental health issues, or your vulnerabilities from your childhood attachment histories. Clearly it is a complex topic and I’m sure the work of scientists like Britton will begin to shed light on the nuances so that everyone can benefit from the positives of meditation at the right ‘dose’ and pacing. Some people never experience this territory, others do for brief periods without major impact to their lives, but some people do get stuck in these modes for long periods of time. Hopefully especially the latter group will benefit from ideas in this post. Feel free to contact me if you have any queries about adverse effects as a result of meditation practice.

I have created the following two videos that explore some of these ideas further: